The species-discharge relationship is analogous to the species-area relationship, and describes how fish diversity increases with river size (Figure 2 McGarvey & Milton 2008). River discharge is the volume of water passing a particular location per unit time. Larger rivers can accommodate larger fish as well as small fish, and so the size range of fish increases as rivers become deeper. Analogous fish community responses to river slope and size have been found in African, South American, and many North American streams (McGarvey & Hughes 2008). 2000) generalized Western European river habitats based upon a predictable sequence of dominant fish species (Huet 1959). The fish zonation concept (Thienemann 1925, cited by Schmutz et al. Predators represent a small but important fraction of benthic communities in rivers of all sizes. Collectors utilize particles in streams of all sizes, but they dominate benthic communities in larger streams where suspended organic matter is common. With less canopy cover in wider streams, shredder abundance is reduced. As canopies open in larger streams, grazers become common with increased periphyton production.

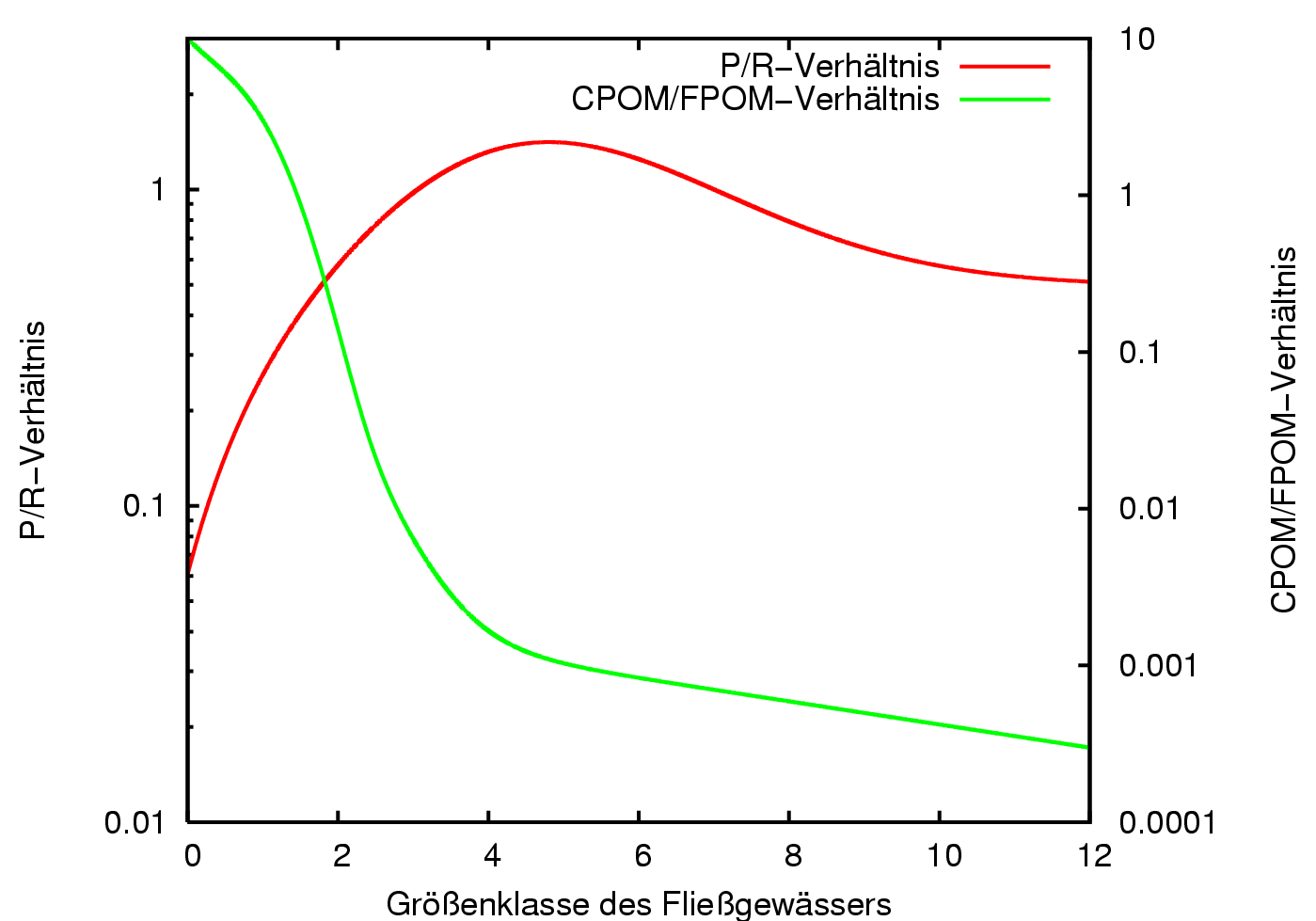

Smaller temperate streams tend to be co-dominated by shredders primarily consuming leaf litter, and collectors consuming particles (Figure 1). Aquatic ecologists classify benthic macroinvertebrates into functional feeding groups: shredders that eat leaves, collectors consuming fine particulates, grazers that scrape periphyton from substrates, and predators of animal prey (Cummins & Klug 1979). Organic matter in suspension is by far the largest food base in these very large rivers.Ĭhanges in physical habitat and food base from river source to mouth profoundly influence biological communities. Water currents keep fine solids in suspension, reducing light penetration to the benthos. Very large rivers are usually low gradient and very wide, resulting in negligible influence of riparian canopy in terms of shading and leaf-litter input. Open canopy, and fairly shallow water, means that light can reach the river benthos, increasing in-stream primary productivity. These larger streams remain well oxygenated because air is entrained by turbulent flow in riffles. Streams at this point are warmer, and less abundantly supplied with leaves than was the case upstream.

This open-canopy state frequently coincides with somewhat lower gradient landscapes. At some point along their path to the sea, rivers have typically gained enough water and width to preclude interlocking tree canopies.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)